Disclaimer: This post is not financial advice. Please consult your financial and tax advisors before making investment decisions. This post is informational and is intended to help you understand the mechanics of stock options.

Say you are working at, or have an offer from an exciting US-based startup. Chances are your compensation package is a combination of salary and stock options. Stock options can give you a stake of ownership in the company and potential upside in the event the company is sold or eventually IPOs. That means you could make money if the company does well!

In my experience, though, stock options are often poorly understood by startup employees. The orbit of your stock option grant includes pages and pages of legal jargon, tax implications, documents you may need to file, and money you need to pay to buy the stock. Compounding everything is timing. When you buy your stock options plays a vital role in your tax burden immediately, and in the future.

There are a lot of moving parts and it can be tough to understand how everything works together. Take a deep breath. This post is here to help give you a reasonably in-depth understanding of the mechanics.

- Stock options overview

- Reasons to not exercise your options

- Sounds complicated, just give me stock?

- Vesting schedule

- Strike price and FMV

- Why do stock options cost money at all?

- Taxes V1: Exercise timing, the IRS, and your wallet

- Taxes V2: Short-term vs long-term capital gains

- Taxes V3: When do you have to pay taxes?

- Early exercising

- Types of stock options

- Post-termination exercise window

- The end

Stock options overview

First things first. A stock option is an option to buy shares of stock, not actual shares of stock issued to you.

Roughly speaking, if you are offered a stock option grant for 1000 shares at a $0.20 strike price, you have the option to buy 1000 shares of stock for $200 (1000 * 0.20). When you exercise (buy) your options, your options will convert to stock. Exercise 1000 options, and you will own 1000 shares of stock. Nice job! Add "company owner" to your resume.

A quick glossary

Before we dig too deep, there are a few basic stock option terms you will need to know.

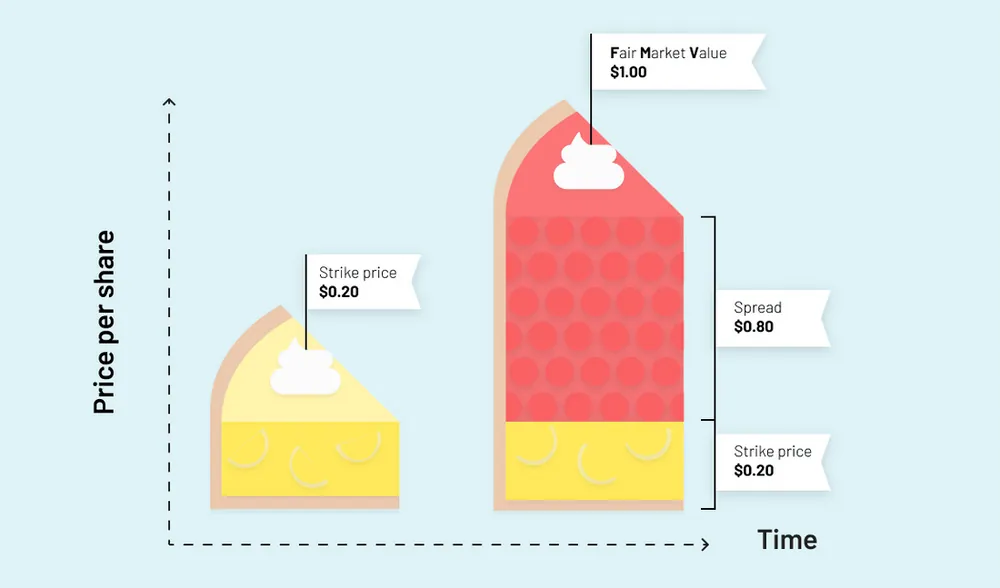

Strike price is specified in your option grant. It is the amount it costs you to exercise the option and buy a single share. In our earlier example you got a 1000 share grant with a $0.20 strike price: each share costs $0.20. It'd cost you $200 (1000 * 0.20) to buy all 1000 shares.

Fair market value (FMV) is the current value of a single share of the company's stock. This will change over time as the company grows.

Exercise is what you do when you buy shares. Your option grant is the option to buy shares, then you exercise that option by buying some number of shares.

Spread is the difference between the strike price and the fair market value when you exercise.

Vesting is when options accrue to become yours as you spend more time at a company. Exactly when the options become yours is dictated by a vesting schedule.

General option mechanics

The strike price on your option grant will never change. Never! Nope! Your 1000 options at a $0.20 strike price will always cost $200 to exercise.

As a company grows, its fair market value will increase, even though your strike price stays the same. If your company grows until the FMV is $10, your $0.20 options are a great deal! You have the option of buying something worth $10 for $0.20. Amazing, right?

This is the double-edged sword of stock options. If you exercise your stock options when the current FMV is higher than your strike price, you may owe taxes on the spread. Taxes! Oh no.

For example, if you buy your 1000 options at a $0.20 strike price and the FMV is $10, the shares you paid $200 for are immediately worth $10,000. Great for you, but the IRS takes their cut in the tax-year you exercise. You will be taxed on a $9,800 gain ($10,000 - $200), or number of shares * (fair market value - strike price). How and where you are taxed depends on the type of stock options specified in your option grant.

Then when you go to sell the stock that you purchased either after an IPO or through an acquisition, you will be taxed again. This time you are taxed on the spread between the FMV at time of exercise and the sale price. Your tax will rate depend on when you bought your options.

What does it all mean?

Generally speaking, if a company grows to be considerably larger than it is when you receive the option grant, the earlier you exercise your options, the less you will pay in taxes. This applies both to the time of option exercise, and to future taxes when you ultimately sell them for cash.

Early startup employees at companies that grow really large can have a precarious tax situation creep up on them. They may have stock options with a cheap strike price but with an extremely high FMV. If they were to exercise their options, the IRS would charge a ton of actual dollars. Potential tax bills in the tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars are not uncommon. Private company shares are not tradable in the same way public company shares are. If the company is still private, a person in this situation could owe real money in taxes on shares that they can't even sell!

Reasons to not exercise your options

The rest of this post will go into more detail on what happens if you were to exercise your options. In the exercise scenario, you believe the company will grow and the value of the shares will continue to increase.

Exercising your options is an investment decision and with any investment decision, there is risk. Exercising your options costs real money. If the company shrinks or goes under, it is possible you lose the money you invested.

If you are not confident the company will grow, feel it's too risky, or you do not want to spend the money to exercise your options, it is totally fine to opt out of exercising your options.

It is not uncommon for employees to wait and exercise their options only at the time of an acquisition or IPO event. That way you mitigate risk, but may have a higher tax bill should the company get to an exit event.

Sounds complicated, just give me stock?

Some companies do offer straight-up stock grants to their employees, usually in the form of Restricted Stock Awards (RSAs) or Restricted Stock Units (RSUs).

RSAs are stock grants where purchasing and taxation happens up front. They can be offered for free ("no cost" RSA), but you would owe tax on the value of the shares at the time of grant. Or they can be purchased at some price up front, all at once when you receive the grant. These are best for very early employees when the FMV is extremely low. If the FMV is $10 and you got an RSA with 10,000 shares, you'd have to either pay $100,000 to buy all the stock, pay taxes on an extra $100,000 income, or some combination of the two. Even though the payment or taxation happens up front, RSAs still vest like other equity vehicles.

RSUs have no strike price, you do not have to buy them. However, they come with their own tax implications. As your RSUs vest, the IRS treats the number of vested shares times the company's current FMV as income. Using our RSA example, you have 10,000 RSUs and they vest at a rate of 2,500 per year. At a $10 FMV, the IRS would tax you on an additional $25,000 income per year (2,500 * 10).

Typically RSAs will be offered only to the first couple people at the company. RSUs are more common at larger, often public companies. A company will usually start offering RSUs when the FMV is so high that buying stock options becomes untenable.

Stock options are a middle ground. They are common at most startups because they come with the least-bad combination of cost and tax treatment for the employee.

Vesting schedule

Continuing with our example of a comp package with an option grant for 1000 shares. You could just quit on day one and those 1000 stock options would be yours, right? So smart! Very tricky! But no, your option package will "vest" over some amount of time. Basically, each month you spend at the company, some number of options from your package will vest, or become yours to purchase.

Your option grant document will have a section outlining a vesting schedule: how many shares vest, or become yours, in some time period. For example, a very common vesting schedule is a four-year vesting schedule, vesting monthly, with a one-year cliff. Let's break this down:

- Four-year schedule: In order for the all 1000 options in the package to be yours, you must be an employee at the company for 4 years.

- One-year cliff: you must be at the company for at least one year to have any vested options. At the one year mark, 25% of the options in your package will vest.

- Monthly vesting: every month after the one-year mark, you will vest 1/48th of your options.

Strike price and FMV

When you are given a stock option grant, the strike price will be set to the current fair market value. For example, say you get a stock option grant when the FMV is $0.20, your strike price will be $0.20. Then a year later, you get another stock option grant. The company has grown and the FMV is now $0.50, you will have two stock option grants: one with a strike price of $0.20 and another with a strike price of $0.50. Note that even though the FMV went up, the strike price on your first grant did not change.

You can get your company's FMV usually by asking your HR department. If you use software that tracks your stock options, generally the FMV will be shown somewhere in that service.

Why do stock options cost money at all?

Can a company arbitrarily set the fair market value and strike price at $0 or $0.0001?

Unfortunately, no. Strike price is based on FMV, and FMV is based on the company's last 409a valuation.

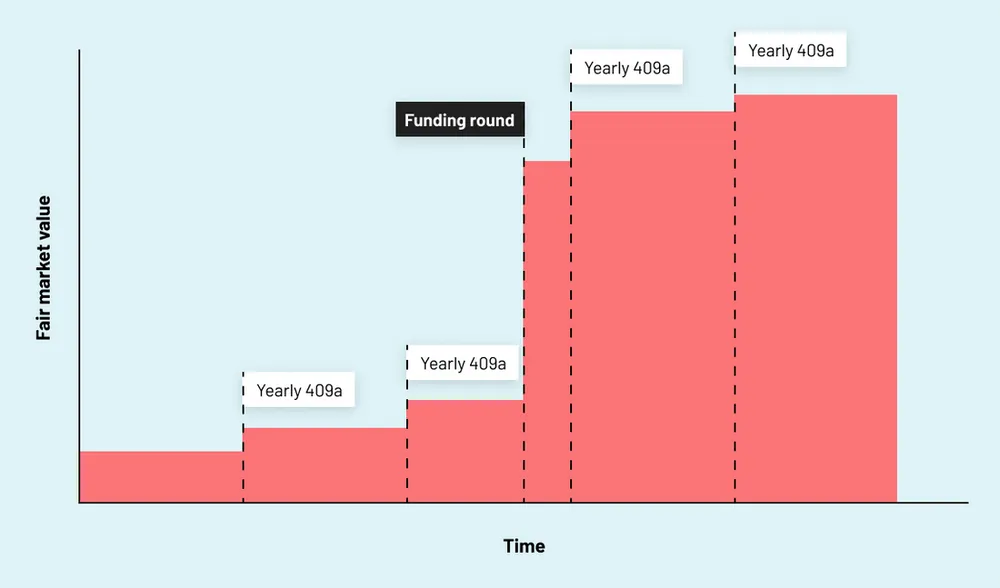

A 409a valuation is when an external party values the company based on its assets, revenue, and other metrics. Then that valuation is divided up by the number of outstanding shares. A company with a $2,000,000 409a valuation and 10,000,000 outstanding shares will have a fair market value (FMV) of $0.20.

The IRS requires companies get a 409a valuation at least yearly, but also when there are major events affecting the valuation like VC funding rounds.

A hypothetical company's FMV over time

A hypothetical company's FMV over time

Is a 409a valuation the same as the venture capital valuation?

No. The 409a valuation has little bearing on the valuation of a company when it is raising money from VCs. It's common for the 409a valuation to be significantly less than the VC valuation. For example, a company could fetch a $30 million valuation from VCs, but have a 409a valuation of only $5 million. You can think of the 409a valuation as being the current value of the company, and the VC valuation being a forward looking valuation.

A low 409a valuation is advantageous to employees because it keeps the FMV low, thereby keeping strike prices and employee tax burden low.

While a 409a valuation does not impact the VC valuation, a new funding round with a new VC valuation absolutely will impact the 409a valuation. A new funding round will usually increase the 409a valuation, which will in turn increase the current FMV, then increase your tax burden if you were to exercise your options.

Taxes V1: Exercise timing, the IRS, and your wallet

Okay, we've covered a number of moving parts up to this point. But what does it all mean for you? Everything comes together to help give you a rough idea of how much you will owe in taxes.

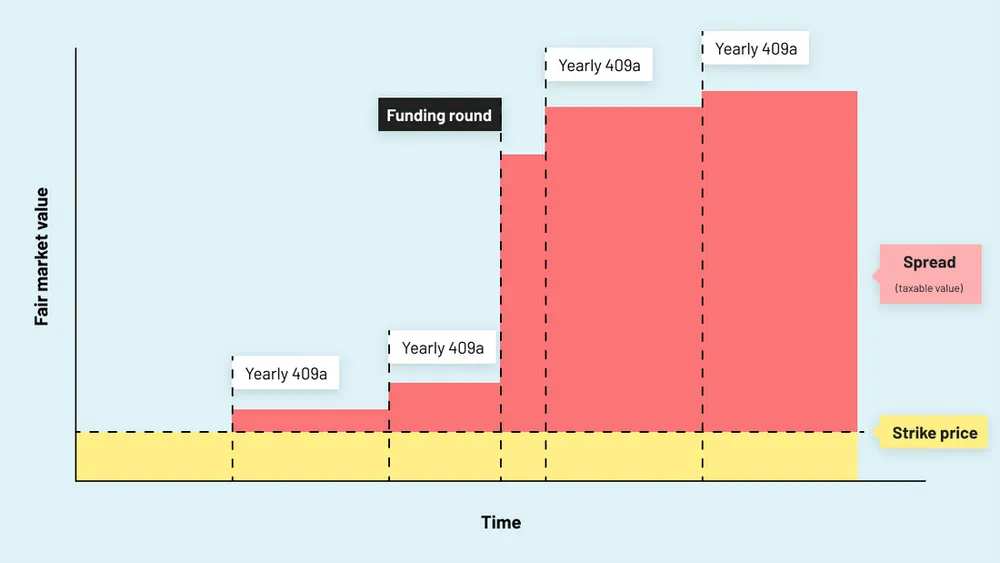

So far we know that:

- You get to buy your options at the strike price.

- Your strike price does not change.

- Fair market value is based on a 409a valuation.

- A 409a valuation happens at least yearly, then absolutely after every new funding round, which will change fair market value.

- In a growing company the 409a valuation will go up over time.

- You are taxed on the difference between your strike price and the current fair market value (spread) at the time you exercise the stock options.

Other than strike price, these attributes are heavily dependent on timing. That is: your tax burden depends on WHEN you exercise your options. Timing can be the difference between owing $0, a little, or a whole lot in taxes.

To distill this down: if you plan on exercising your stock options and the company increases in value over time, exercising earlier is usually more tax-advantaged. This is especially true because FMV is a step function. FMV will be flat between 409a valuations, then can significantly increase after the next 409a valuation.

As the company grows, FMV, and therefore amount you are taxed on goes up

As the company grows, FMV, and therefore amount you are taxed on goes up

Depending on your option grant specifics and the jumps in FMV, even one month could mean thousands more dollars in taxes.

Taxes V2: Short-term vs long-term capital gains

But wait, there's more! The timing of when you bought your stock options can also impact your future taxes. When you exercise, you are purchasing shares with the intention of one day selling them for more than you purchased them.

Say you exercise your options, the company IPOs, then you sell your stock in the public markets. The IRS will charge you tax on the spread between the FMV when you bought the options and the price you sold them for.

In this scenario, the amount of tax you have to pay depends on the length of time between buying the shares and selling them. If you hold on to them for over one year, you qualify for long-term capital gains tax, which is taxed at a significantly lower rate than short-term capital gains.

Zero federal tax? A note about QSBS

It is possible to pay $0 in federal tax when you sell your stock for cash. For real.

If the stock in your company meets the requirements for qualified small business stock (QSBS), then you could potentially be 100% exempt from capital gains tax. There are several requirements, but the big ones are:

- You must hold the stock for 5 years from the time you exercise your options and convert them to stock.

- The company must have less than $50 million in assets at the time of exercise.

Taxes V3: When do you have to pay taxes?

The basic gist is: when you exercise options, any taxes you owe are due for the tax year you exercised the options. If you exercised options in 2022, you will owe tax on them in 2022. They will be on your 2022 tax return when you file your taxes in 2023. But wait, it gets trickier!

If you are a salaried employee, you are probably used to filing a tax return at the beginning of the year for the prior year's earnings, then getting money back from the IRS: a tax refund. As a salaried employee, each paycheck has a "federal withholding". That withholding is going to the IRS to prepay taxes you may owe at the end of the year. You get a refund because you prepay more than you actually owe in taxes.

The IRS has a thing called an underpayment penalty. If you do not withhold or prepay as much as you will owe in taxes, you will have to pay the IRS what you actually owe in taxes plus an extra penalty. If you only receive a regular salary, this is all kind of handled for you with the federal withholding. Salary-only employees usually don't underpay.

If you exercise options, though, you have to manage prepayment on your own (or with your tax person). When you exercise options and there is a spread, you may owe taxes, and those taxes you owe may add up to be more than you are currently withholding from your regular salary. If you think they are more than you are withholding, you need to prepay. If you need to prepay, it needs to be in the same year you exercise options, otherwise you will face an underpayment penalty.

Whew, okay, let's recap with a couple scenarios. Say you exercise some number of options:

- They do not actually increase your tax burden. No prepay!

- They do increase your tax burden, but it is less than you are already withholding from your salary. No prepay!

- They do increase your tax burden, and it is more than you are already withholding from your salary. You need to prepay.

It is possible to exercise options, even when there is a spread, and not have to prepay extra to the IRS. There are a lot of variables here. You should walk through your scenario with a tax person to figure out if you need to prepay and how much.

Early exercising

Early exercising is the process of exercising stock options before they have fully vested. Even though all the stock options are not yours yet, early exercising allows you to buy some or all of them and pay the tax now. If you have early exercised and leave the company before all your shares have vested, the company will pay you back for the unvested shares.

Provided the company grows, the most tax-advantaged, and also the most tax-simple scenario is exercising an entire option grant immediately after receiving it. Since you had just received the grant, no shares would be vested, but early exercise allows you to purchase them all. In this scenario, two things would happen:

- You pay nothing in taxes at the time of exercise because the strike price and fair market value are the same. The spread is $0. Timing!

- You start the clock on long-term capital gains.

- For companies with assets less than $50 million, you start the clock on the five-year holding window for qualified small business stock (QSBS).

If your company allows it, early exercising can happen some time after you have received the grant, even after the FMV has changed. If the FMV has changed, it's possible that you may owe some taxes at the time of exercise because of the spread.

Note that not all companies allow early exercising option grants. Ask your HR department about it!

Filing an 83(b)

If you early exercise unvested shares, you can file an 83(b) election. The election tells the IRS that you have paid taxes on all unvested shares in the current tax year saving you on taxes later on when you go to sell the shares.

How do you file an 83(b) election? Anvil offers a free 83(b) form that will generate an 83(b) election you can mail to the IRS.

Types of stock options

We now know that when you exercise options, you are taxed on the value of the spread: the difference in value between the strike price and the fair market value. Or more concretely, taxable value = number of shares * (fair market value - strike price). The way the IRS counts taxable value as taxable income depends on the type of stock options you received. Your stock option grant legalese will call out which type of options you have received.

Incentive stock options (ISO) factor the taxable value into alternative minimum tax (AMT). AMT is calculated in parallel to regular income tax, not directly added on to regular income tax. Then you pay either regular income tax or AMT, whichever is higher.

If your taxable value from your ISO option exercise is small enough, you may not need to pay any additional income tax! That is, it's possible to buy just enough shares that it will not impact your taxes at the end of the year. Calculating AMT is complicated, though. Consult your tax person if you are curious how much taxable value keeps you within your regular income tax.

Non-qualified stock options (NSO) are more straightforward. The taxable value is factored into regular income just like your cash salary. Simple, but can lead to a higher tax bill.

Post-termination exercise window

Say you plan to leave the company after vesting some options. What happens? First you only get to keep options you have vested. Then, if you have not already exercised all of your vested options, you will need to think about your post-termination exercise (PTE) window.

What the PTE?

When you leave, there will be some window of time you are allowed to exercise your vested, but un-exercised stock options. If you do not exercise them, un-exercised vested shares go back to the company. To be clear, you will get to keep all exercised and vested options, but will need to make a decision on your un-exercised and vested options.

If you have ISO stock options, the max time window is 90 days. Put another way, you have only 90 days after leaving a company to exercise all vested options. In companies I've worked at in the past, my coworkers have been frustrated with the company for only giving them 90 days. Ninety days is such a short time! Jerks! I worked here for five years!

But it turns out, 90 days after termination is actually the IRS limit for the tax treatment on ISO options. Many companies would love to give you a longer window, but the IRS dictates a maximum window of 90 days.

Some companies offer a longer window

The 90-day window is changing and many tech companies are now offering longer windows. The rub is that in order to give a window longer than 90 days on your ISOs, the company will convert ISO options to NSO options after 90 days. NSOs do not have the same 90-day limitations.

It is great that you get more time, however, NSOs have a different tax treatment. NSOs are taxed as regular income, and this can be more than you would pay in taxes after exercising the same ISOs.

Planning is key

If you have ISOs, be aware of your own PTE window. If you are looking to leave your company, it's helpful to come up with a plan before leaving. Do you want to exercise your options? How many? What will your tax burden be?

There are plenty of employees at hyper-growth companies who have had to forfeit vested stock options because they could not afford to purchase the shares, or the tax bill after purchasing them. Hopefully some planning before you are subject to a time window will keep you out of this scenario.

The end

That was a lot, but you made it. Great job! Now the (potentially) million dollar questions are: Should you exercise your stock options? If so, when should you exercise them?

No blog post can answer these questions for you! Everyone's situation is different. The vast landscape of company stages, option grant details, your risk appetite, and your own financial situation make your move only for you to determine.

This post should give you an overview of most of the factors that go into a decision. The tradeoff you're ultimately making is risk of losing your investment vs potential tax burden. The earlier you exercise your options, the better the tax treatment, but the more risk you are taking on. It is helpful to walk through different scenarios with your tax person and come up with a plan.

Let us know if you have any questions or comments at hello@useanvil.com.